How to disappear completely

Caffeine as a gateway drug, part nine: pharmacokinetics

If you’re new to Lessons on Drugs, welcome! This is post number nine in the Caffeine as a Gateway Drug series, where we explore how drugs work by looking at the world’s favourite drug, caffeine. In this post we’re focusing on pharmacokinetics, which sounds very technical and boring, but is actually super relevant and a really good way of bringing everything we’ve covered so far together into an overall understanding. How the drug hits its peak and then disappears…maybe completely, maybe not, depending on the drug and what it’s used for.

The challenge I’ve set myself is to try and explain how drugs work in enough detail to provide a proper explanation, without requiring people to have a heap of pre-existing knowledge about how the body works, ‘dumbing things down’ and being condescending. I’ll admit, this week has been hard, but I’ve given it a red hot crack!

In the previous posts, we’ve introduced a whole bunch of concepts relating to how drugs work in the body. Just to show you that we have indeed covered most of the fundamental concepts, here’s the boring textbook like list of formal concepts that have been covered so far:

Bodily logistics - fundamental physiology

Part 1 - general introduction

Part 2 - dose, formulation, route of administration, absorption

Part 3 - well, this was a bit of a rant, but covered dose-effect relationship, local vs systemic effects

Part 4 - pharmacology of drug-receptor interactions

Part 5 - metabolism and pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions

Part 6 - physicochemical drug interactions

Part 7 - pharmacodynamic drug interactions

Part 8 - drug elimination

But I don’t want this to read like a textbook. And so…it’s time for a music analogy.

I was brought up in a household that always made space for music. Saturday morning cartoons could barely be heard over Dad’s choice of classical music record played at excessive volume. Family car trips were a similar deal, but then we were tormented with opera. Needless to say, the year I got my Sony Walkman for Christmas was a game changer.

I had (still have) the privilege of an older brother with an extensive music collection. Mixtapes abounded. And so it was that my musical taste closely followed whatever he was interested in during my formative years. One of the few exceptions to this was my insistence on getting the Snow CD for the Christmas of 93. With such hits as, Informer, and…nothing else. I don’t subscribe to that whole ‘no regrets’ mentality. That was 100% a waste of a Christmas present.

I made good use of my Christmas present of 97 though, with tickets to my first international concerts. The plural is not a typo because it was not one, but two! February 1998 was amazing- it started with Radiohead and closed with Oasis.

One of the things I enjoyed most when it came to seeing Oasis was Noel’s acoustic set. I didn’t get to hear my favourite Half the World away, but he did perform Don’t go away (my preferred version to the usual Liam version) and Setting Sun, a Chemical Brothers cover. The concert closed with another cover- the Beatles I am the Walrus.

Don’t go away is in one of extremely limited repertoire of songs I clumsily strum on the guitar. Unfortunately, my skills in playing music don’t live up to my aspirations. I’m pretty good with theory, but I just don’t have the dexterity and musicality to pull off much more than a few cowboy chords to sing along to. I like to think I make up for it with performance.

One of the things you learn about early on in music theory is time signatures. The clap your hands to different rhythms type activity you do with little kids sitting in a circle. It’s the underpinning foundation of every song. Something with three beats to a bar will feel fundamentally different to something with two, four or eight beats. I say feel because I surely can’t be the only one who’s experienced that awkward moment on the dancefloor at a wedding when the makeshift DJ doesn’t quite manage a song transition smoothly.

Most cover versions of songs involve a change in musical arrangement or tempo rather than messing around with the time signature. Noel’s acoustic set certainly aligned with this. The songs feel a bit different, but still very familiar. There are lots of good examples of this. Frente!’s version of New Orders Bizarre Love Triangle. Sinead O’Conner’s version of Prince’s Nothing Compares 2 U…let me know your favourites in the comments.

Far less often, an artist will reinterpret a song altogether by performing it in a different time signature. A good example of this is Joe Cocker’s version of the Beatles’ With a Little Help From My Friends. Some people far cleverer than me even figure out a way to change the time signature seamlessly within a song - like Otis Redding’s version of Billy Hill’s Glory of Love.

What I’m trying to convey here is that the arrangement of instruments, the speed in which it is played (tempo), and the time signature are fundamental properties of a song. If we play around with any of these aspects, we can change the way we experience that song.

And just like there are certain features we can play around with to get a song to feel different, so too can we change the way a drug makes us feel in our body by changing certain elements.

The amount of drug in the body over time

Before we get into the details, let’s make sure we’ve got the basics down first.

I’m sorry, but my writing isn’t strong enough to convey a picture as good as showing a graph and explaining what it means. You don’t need to understand the math, just the shapes. If you really hate maths and looking at graphs, you can watch this poorly made video:

Get excited, this is going to bring together all the concepts we’ve introduced over the past eight posts. I know, pharmacokinetics is the best! Let’s start with what the graph is showing - the amount of drug in the body and how it changes over time.

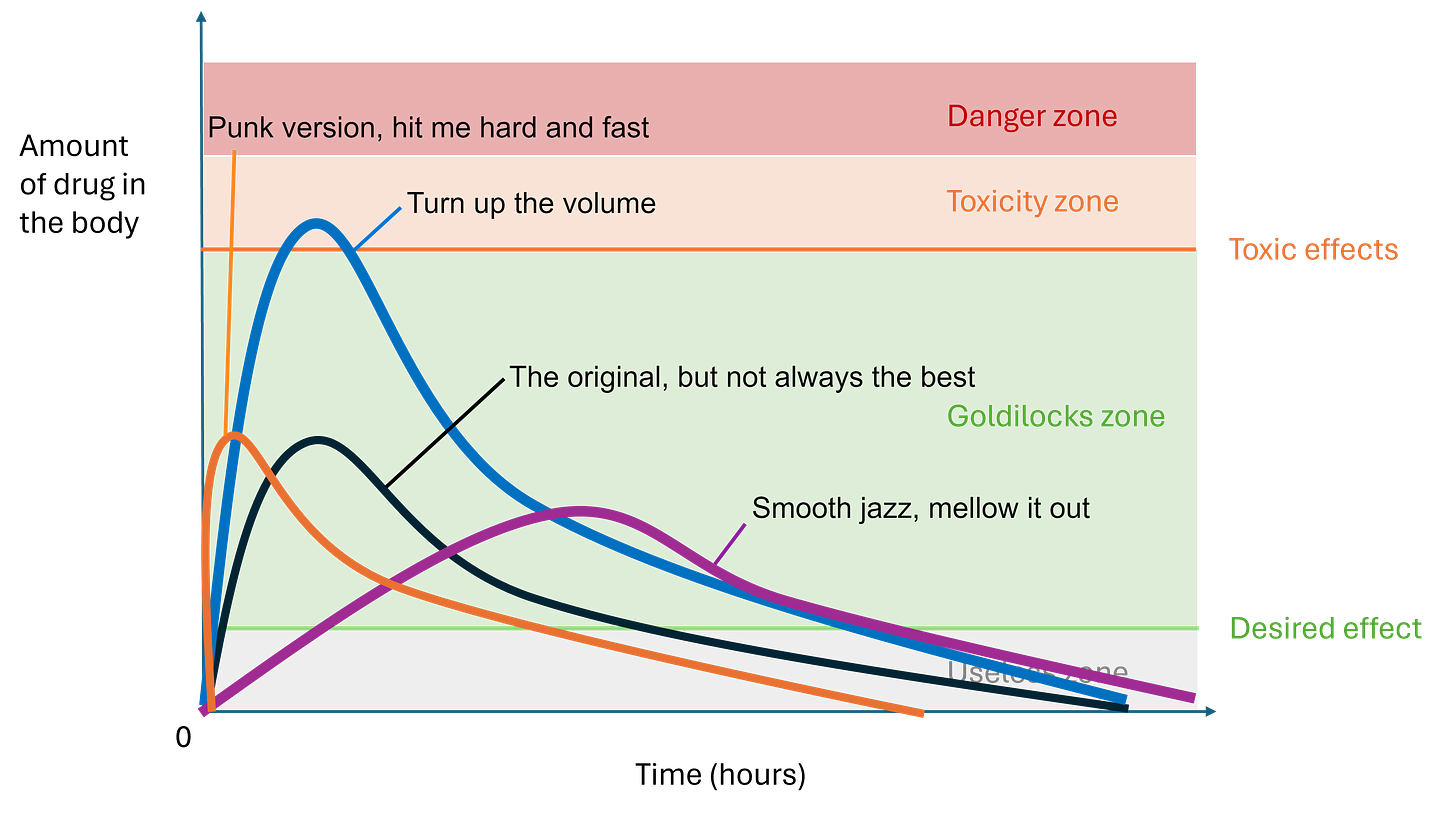

As we talked about in part three, for a drug like caffeine, the effect in the body is proportional to the amount of drug in the body. The desired effects of caffeine are most likely the mental alertness, or perhaps the performance enhancing effects. On the graph below, the amount required to produce the desired effect is shown by the green line.

If the amount of caffeine in your body is below the green line it won’t be enough to produce the desired effect. But be warned, it might still be enough to produce an adverse effect. The sceptics would say this is why caffeine is in Coca-Cola - its not enough to give people a buzz, but it is enough to act as a reinforcing agent that keeps people coming back for more. We’re going to call the part of the graph below the green line that’s shaded grey ‘the useless zone’ just to drive home the point that if you’re going to use a drug, use it at an appropriate dose to cause the desired effect.

High amounts of caffeine can result in what we call dose related adverse effects, represented on the graph by the orange line. It’s better to avoid getting to these amounts because this is where toxicity happens - we’ll call this the ‘toxicity zone’.

Push the amount even higher and you move from the toxicity zone into what we’ll call the ‘danger zone’, represented on the graph by the red area. When there is an excessive amount of a drug in your body, it can result in effects in the body that don’t occur at usual doses. This can be lethal. Our mission is to keep clear of the danger zone entirely for all drug use. No one should die because of the drugs they take.

When we use a drug for a therapeutic purpose, we’re aiming to achieve an amount of drug in the body that’s ‘just right’ - we’ll call this the Goldilocks zone, represented on the graph by the area shaded green. We want to keep the amount within that zone for an amount of time that’s fit for purpose. For instance, by the time I’m ready to go to sleep, I want the amount of caffeine in my body to be way below the green line.

The black line on the graph represents the amount of drug that’s inside your body and able to exert an effect. As we talked about in part six, if you have a cup of coffee on an empty stomach, it starts moving into your bloodstream within a few minutes and is fully absorbed within about an hour. This is what we call the peak amount of drug in the body. From this point on, the amount starts to reduce as the caffeine gets eliminated by the body by the liver and the kidneys, which we covered last week. The caffeine keeps getting eliminated until it reaches a minimum amount, which we call the trough.

The time that the amount of drug in the body is in the goldilocks zone is the duration of action.

This overall picture of the amount of drug in the body over time - the peak, the trough, the duration of action - impacts how it makes us feel. Now that we’ve got that covered, let’s walk through how we tweak different elements to get the drug to sing in the body in different ways.

1. Change the arrangement

We’ll start by thinking about the most common way of covering a song - changing the arrangement. To change the arrangement of this drug regimen, we need to think about the concepts introduced in part two - dose, the formulation, and route of administration.

Just like the earlier graph, the black line on the graph below represents the original version of the song - a standard shot of espresso consumed on an empty stomach.

One option you might go for is to turn up the volume by increasing the dose - have a double shot espresso instead of a standard one. This will result in a higher peak which is represented in the graph by the blue line. A higher peak might be ok, but it runs more the risk of pushing the amount to levels that produce dose related side effects like the jitters and anxiety.

Turning the volume down by reducing the dose has the same type of impact in the opposite direction. It will reduce the peak, but the rate of absorption and elimination remain unchanged. This isn’t shown on the graph

Another option you might take is to soften things out and do a smooth jazz version - something that slows down the absorption so the drug moves into the bloodstream more gradually. This is represented by the purple line. Slowing down absorption produces a smaller peak, which helps to reduce the side effects for some drugs. As we covered in part six, one way of slowing absorption is by having food in your stomach. The other method is by choosing a different formulation, like a slow release tablet or capsule. This can also extend the duration of action.

The other cover version that is screaming to be made, is the punk version - something that speeds up the absorption and moves the drug into the bloodstream faster. This is represented by the orange line that shifts curve slightly to the left with the same peak and trough. The best way of achieving this is to change the route of administration, many of which were covered in part three. (Given it’s punk, I’m thinking this is where the snorted caffeine would come in, but I shouldn’t stereotype).

2. Change the time signature

Now, lets shift our thinking to a cover version of a song that involves a different time signature. This type of cover version occurs much less frequently. I went down a rabbit hole for too long on this one, and I couldn’t find any other examples than the two mentioned earlier.

We’re going to relate this to the half life of the drug in your body. That’s the term we use for the length of time it takes for the concentration of drug in your body to reduce by half. The usual half life for caffeine is around 4 to 5 hours. Again, the usual scenario (OG version) is represented on the graph below by the black line.

A general rule is that within five half lives, enough of the drug has been removed from the body that it’s considered to be eliminated from the body.

100% → 50% = 1 half life

50% → 25% = 2 half lives

25% → 12.5% = 3 half lives

12.5% → 6.25% = 4 half lives

6.25% → 3.125% = 5 half lives, which is close enough to gone.

They figure out what the average half life of a drug in humans is through clinical trials - the type where healthy but poor university students take a dose of a drug and have blood levels taken. The key words here are healthy and average (plus likely young and male). In other words, if multiple people are given the same dose of drug, we can expect them to each have a slightly different half life.

The half life of a drug within your body will be influenced by how well your body eliminates it. As we talked about in last week’s post, there are two main components of elimination: metabolism by the liver and elimination by the kidneys. Drug interactions like those described in part five can increase or decrease half life. Otherwise, it’s unlikely to change much on a day to day level unless you have a major health event like kidney failure. An extended half life is shown on the graph by the orange line - you can see that it hangs around for much longer.

Because of this, half life can be considered like the cover song with a change in time signature - not something that will change regularly within the same person. Tempo, however, is a different story.

3. Change the tempo

Our last cover version is the change in tempo. A good example of this is the Gary Jule’s (Donnie Darko) version of Tears for Fears Mad World. In music, this is usually done hand in hand with a change in the arrangement, but we’re going to focus just on the tempo and we’re going to relate it to how regularly a dose of a drug is given.

The scenarios we’ve talked about so far have all been concerning a single cup of coffee, or dose of drug. We’re now going to look at what it’s like if I have that same cup of coffee multiple times throughout the day - so no change in dose, formulation or route of administration.

Say I have a cup of coffee with my breakfast at 6:30am. The half life is around 4 to 5 hours, so by 10:30am there’s around half the amount of caffeine I originally ingested remaining in my body. If I have another coffee at this time, I’m adding to the amount that remains in my body. If I have another coffee with lunch at 1pm, I’ve still got caffeine remaining in my body and I’m adding even more. I’m putting caffeine into my body at a rate that’s faster than the rate I’m getting rid of it. This results in an increased amount of caffeine within my body which can push the levels closer to that toxicity zone. I’ve tried to illustrate this in the graph below, but keep in mind it’s not drawn to scale or trying to be exact - it’s hard drawing curves!

If we give a drug for a medicinal effect, we time the frequency (what we call the dosing interval) to keep the overall amount of the drug within that goldilocks zone. If you take a medicine at the same dose regularly, it achieves what is known as a steady state concentration - this is where the amount going into the body is roughly the same as the amount being eliminated from the body. The math goes that steady state is achieved in 5 half lives when something’s given at regular dosing intervals. This is illustrated in the graph below - again, not an accurate depiction, just to demonstrate the concept.

Remembering that the half life of caffeine is around 5 hours, I think it’s reasonable to say that unless you’re some sort of psychopath who consumes caffeine every 5 hours and never sleeps, you’re unlikely to find yourself at steady state any time soon. With that in mind though, if you’re having trouble getting to sleep at night, or needing to get up and pee through the night, it might be worth thinking about your caffeine consumption during the day and if it’s still hanging around in your body. Personally, if I drink coffee after about 11am, it impacts my sleep. Which, let’s be honest, I sometimes use to my advantage - I’m not exactly a rager these days so I need some help staying awake after 10:30pm!

This brings us to the end of the Caffeine as a Gateway Drug series! Well, maybe. I’m interested to hear from you if there’s anything else you’d like to know about. Is there a concept that’s still confusing? Or maybe something I missed altogether?

Thanks so much for reading Lessons on Drugs. If you enjoyed it or found it interesting please give me a like, restack or share through the platform of your choosing - more importantly than feeding my ego is that it helps other people find it. And call me idealistic, but I really think it’s important for people to learn about this sort of stuff to stay healthy and avoid harm.

Ok, there are no more requests, I promise. I’ll close with the musical reference in the title…there was a moment where I contemplated doing an acoustic Weird Al Yankovic style parody version of this song about what we’ve learned about caffeine, but I couldn’t bring myself to put you all through it!

I finally finished the series, it was great, thank you! (It only took me so long because I send tons of posts to my Kindle and articles get buried behind other ones, and I use Instapaper, so there's a mishmash of totally unrelated posts and it's kind of luck of the draw with what I read every day).

I've learnt a lot here and I'm curious, unless I missed it, what your coffee habits are like now. Because of my sleeping issues, I probably should cut down but I can't function without it (yes, I can see the problem here!). I don't think I'm overdoing it...similar to Tim and his 3 large mugs, I have 2 large mugs a day, and I try to finish before noon. My first is around 9, the second at 11(ish). I sometimes start my day (8.00ish) with a cup of black tea. I start fading fast around 4-5pm.

Anyway, I don't need to give you an in-depth analysis of my caffeine consumption 😂

If you like Frente’s cover, check out Iron and Wine’s version of Love Vigilantes.