Attack on the copycats

Sigourney Weaver and the Killer Drugs, Part Three: Cytotoxic agents

This is part three in Sigourney Weaver and the Killer Drugs series, where we use her movies to understand how antibiotics, antivirals, and cytotoxic drugs work. You can read the introductory post here, find the antibiotic post here, and the antiviral post here. In this post, we’re talking about cytotoxic drugs.

I’m going to start by saying I think the whole romanticising of serial killers is pretty messed up.

I can see how people get drawn into true crime though. I remember reading In Cold Blood when I was younger and being enthralled. It was just like you see in the movies, only a true story.

But nowadays, it’s the ‘true’ bit of these stories I find disturbing. I can’t help but think about all the very real people who were harmed by these experiences. The communities that were terrorised. Not for me, thanks.

The reason I’m stating this upfront is because the movie forming the anchor of the post, Copycat, is all about serial killers. And, truthfully I’m having some regret about my choice. To the extent where I explored whether I could sub in the Copycat episode of the best children’s TV show ever made instead1. But, if there’s one thing more on the nose than talking about serial killers, I’d say it’s talking about how we might bring about Bluey’s demise.

So, attacking serial killers it is.

Eradicating (fictional) malfunctioning humans

In the movie Copycat, the hunt is on to track down a psychopath who is replicating the murders of renowned serial killers in San Francisco. For the purposes of this post, lets think of this as one malfunctioning human being replicating the atrocious actions of other malfunctioning humans. The result is bad news.

I’m going to ask you to use your imagination for a moment and consider the scenario where a large population of malfunctioning humans (serial killers) are living in San Francisco at the same point in time. Terrifying thought, I know. What is even more terrifying is that these malfunctioning humans have the ability to result in copycats, spreading the harm and terror if they’re left unchecked.

They need to be kept under control. Quickly.

Dare I say it though, the size of this population, the harm being caused, and the rate of growth is so dangerous that the best option to make the streets of San Francisco safe again is eradication rather than control. I don’t want to commend violence, but they need to be taken out.2

One obvious solution would be to use some sort of weapon of mass destruction. This is guaranteed to eradicate all the malfunctioning humans in one fell swoop. But I’m not sure it’s the result we’re looking for if the action results in the mass murder of innocent people. Let’s rule this out as an option right now.

Another option is to target people who meet certain criteria. Based on the evidence, if you target white males between the age of 25 and 40 of moderate to high intelligence, you’re probably going to successfully eradicate the vast majority of malfunctioning humans. This is going to be very unfortunate for the much larger number of humans who also fit within this demographic category and are functioning in a way that positively contributes to society. This method will also leave a proportion of malfunctioning humans left unscathed, who will then remain capable of doing harm and inspiring further copycats.

Another approach that could be effective is to target some sort of process that you know a large proportion of the malfunctioning humans use. Say, a major throughfare, perhaps? Again, this isn’t going to be great news for the many other perfectly functional people who also use this thoroughfare. And, just like targeting people based on demographics, you’re not going to get everyone.

I think it’s pretty clear that neither of these solutions are ideal. Both result in collateral damage to innocent people. Both are limited in their effectiveness.

And yet, in some circumstances, these approaches might be necessary. It may even be appropriate to use both together. The trick is, to do this in a way that maximises kill rate and minimises collateral damage.

Attacking malfunctioning cells

Alright, that’s enough serial killer talk, it’s time to bring it back to healthcare.

This post is about how we use drugs to attack human cells that are malfunctioning and replicating out of control…also known as cancer cells3.

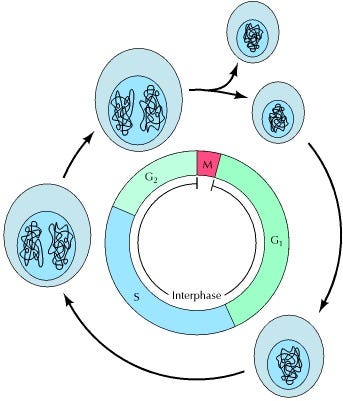

Human cells grow in number by making copies of themselves. This occurs through a stepwise process called mitosis, illustrated in the figure below.

Normal cells have tight controls over how rapidly they divide. Various growth factors and signalling molecules provide feedback loops that trigger cellular death (apoptosis) and division (mitosis).

Some cells are different though. They have DNA that’s mutated in a way that makes these usual control mechanisms malfunction. These malfunctions can result in cells that have an abnormal lifespan, divide at an abnormal rate, or some sort of combination of the two.

Cancer cells have mutations that enable them to be very effective at making copies of themselves. But, thankfully, they also have mutations that make it (somewhat) easier to trigger cell death. This is where traditional cytotoxic drugs come in.

Before we get into it, I want to point out that contemporary cancer care involves many more drug treatments than traditional cytotoxic drugs alone. Some people might think of these globally as ‘chemotherapy’, however there is also hormonal therapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy which have vastly different side effects to traditional chemotherapy4, which is the focus of this post.

Traditional chemotherapy drugs are cytotoxic, meaning they work by killing cancer cells. Now, just as I proposed two different approaches to killing the malfunctioning humans, there are two main ways that cytotoxic drugs work: target a specific phase of cellular division, or act globally on dividing cells. And just like in the serial killer scenario, both approaches come with limitations in effectiveness and inevitable collateral damage.

Drugs that act on a specific phase of the cell cycle can be thought of in a similar way as the approach to eradicating malfunctioning humans that targeted the busy thoroughfare. Highly effective for killing human cells that are in that particular phase of the cell cycle but it includes killing normal human cells that are in that phase of the cell cycle too, resulting in side effects.

Drugs that act on the cell cycle more globally are a bit more ‘heavy hitting’, like the approach that takes out an entire demographic group including the great many who are positively contributing to society. As such, they’re highly effective in killing cancer cells, but they too kill a lot of normal human cells, resulting in side effects.

The types of side effects that can be expected with cytotoxic drugs tend to be associated with cells that naturally divide at a faster rate. Think of the things that regularly regenerate and grow back quickly when damaged - your blood cells, skin, hair, fingernails, nerve fibres, and mucosal lining (the epithelial layer of cells that covers everything including your gut from your lips to your anus, your airways from nose to lungs, your urinary system from urethra to bladder, ears, and genitals).

Thankfully though, the side effects are typically dose related, meaning we can limit the collateral damage by using ‘just enough’. While it used to be a ‘more is more’ approach where they would give everyone enormous doses of chemotherapy and see who survived, advanced knowledge of cancer types, combined with newer forms of treatment mean the goal is now to find treatment regimens that kill the cancer, while minimising toxicity.

So, if you’re facing the prospect of cancer treatment, I implore you - don’t base your decisions on what you’ve seen other people go through in the past, or what you’ve seen in the movies. Instead, ask questions and get informed. Cancer care is a rapidly evolving space and a great deal of research and effort by clinicians is going into making sure treatment is suitable for an individual’s needs. Help your doctors understand what’s important to you, so you can make well informed decisions together.

Thanks so much for reading Lessons on Drugs!

If you enjoyed reading this, please do me a favour and hit the like button. It helps people find it and gives me some encouragement, which comes in handy some days. Sharing this post with others is also very helpful.

The series I’m talking about is the Australian marvel that is Bluey. Some of the most wonderful storytelling in 7 minutes of animation. Hard for me to choose a favourite, but maybe this one.

We know this from every zombie movie and TV show that’s ever been made. Never leave the zombie ‘detained’. Put a bullet through it’s brain and be sure it’s no longer a threat.

Cytotoxic drugs can also be used for non-cancerous conditions, like ectopic pregnancy, and autoimmune conditions. The doses used in chronic conditions is typically much lower than those used in cancer.

Examples of non-cytotoxic medicines used in cancer treatment include hormonal agents (like tamoxifen and anastrazole for breast cancer, bicalutamide and goserelin for prostate cancer), immunotherapy (like monoclonal antibodies - drugs that end in ‘mab’, and immunomodulators) targeted therapies (such as the growing list of kinase inhibitors (most drugs that end in ‘inib’, thalidomide for myeloma).

Great post again Lauren, thanks for explaining, feel like I wanna watch that movie now, and Bluey , not seen either 😁

Very interesting.

I’ve read and listened to interviews with clinical physicians who use ketosis in their patients to help protect the normal cells. Apparently, if the patient is fat adapted and able to stay low carb, cancer treatments are able to better target the miscreant cells and the ones they want to keep are a little safer.